Harry and May Davis – Crowan Pottery

‘Simplicity! What a hard thing to achieve.’

Harry and May Davis met at the Leach Pottery, St Ives, and were married in 1938.

They set up Crowan Pottery in the mill house in Crowan in 1946, and stayed until 1962, when they left for New Zealand and opened the Crewenna Pottery near Nelson.

They were eccentric, idealistic and immensely practical, producing functional pottery of great beauty out of very fine stoneware, or porcelain, often decorated with brushwork or wax resist.

All of Crowan and Crewenna output was marked with the same pottery seal shown here, but not always as clearly! The Davises saw their potteries as workshops – not studios – so to them the whole concept of signed work was inappropriate, and only the workshop seal was used.

On some Crowan porcelain we have seen the impressed ‘P.’ mark, shown here, next to the pottery mark. This indicates the piece is porcelain. Perhaps necessary as from the pottery, porcelain had a 25% price mark up over stoneware.

Unknown to us are the impressed ‘II’, ’12’, ’22’ and ‘B’ marks shown here. We have found these on stoneware plates and bowls made at Crowan.

Please get in touch if you have more information on these marks.

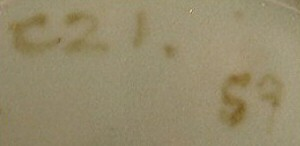

Sometimes, painted glaze marks (C21 here) and body mixture marks (59 here) can be found on (mostly Crewenna) pots. These handwritten numbers mean that the glaze or the body of the pot was a test. Only test pots had this numbering and every firing would include a few tests so that the constant experimentation with different glazes and bodies was continued to improve the aesthetic, strength, and crazing properties. Some of these test pots were then sold.

Harry and May never used personal marks on their work.

In the words of Harry and May Davis

“When we were setting up the pottery at Crowan in 1946, we wanted to broaden the current concept of quality with regard to pots and to couple this with something which has since acquired the name of an ‘alternative life style’.

We were looking for rewards and forms of income which were not connected with money. This led to the digging and processing of a large proportion of the raw materials, which greatly added to interest in the doing and also to the quality of the pots.Quality, we felt, must be extended beyond the narrow obsession with aesthetics which so dominated the craft potting scene at the time. We also intended to take a more integral view of the potter’s role, so that plate making, for instance, became a normal part of a potter’s function. Today few people realise what a novel idea this was in the 1940s and 1950s, when potters neglected plate making altogether.

The stimulation at the back of all this came from our awareness of the fact that traditional potters in numerous cultures and at many different periods had been able to make pots of a highly inspiring and imaginative quality for the simple purpose of domestic use.

We had a strong preference for a rural situation because of the many economic alternatives which country life offered. In this context ‘small’ was seen to be beautiful, even in 1946. A more creative way of working tended to raise the cost of production, and to offset this we endeavoured to give the pots the maximum durability. Indeed, the strength of our pots became something of a legend.

The ‘alternative living’ side offered its rewards in producing the family milk supply from goats and in using the water-wheel to process the raw materials and to provide light and heat. It made possible the production of hay to feed the animals in winter, and provided packing material for our pots the year round. A supply of garden produce goes without saying. The material and psychological satisfaction of all this was considerable.

Apart from tiles, we limited our pots to those which could be made on a wheel. The bulk of our work was stoneware with some porcelain, and the preferred decoration was wax resist, with more recently a good deal of incised decoration.”

Some extracts from May Davis’s autobiography

Crowan mill had seen better days. In 1946 it was milling just cattle fodder and that only once a week, but the water-wheel turned; it worked.

The big stone mill building and the house adjoining it were solid indeed. In true Cornish style, the house walls were about two feet thick and the roof was slate.

At the front was a hoist powered by the water-wheel for taking the sacks of wheat (and later clay) up to the fourth floor.

There was no electricity or water. Candles and oil lamps were fine and water from the stream was good for washing. Drinking water we fetched from a spring at the vicarage down the road.

The old mill made a wonderful workshop. The clay went to the top floor via the outside hoist, powered by the water-wheel. Here it was processed, mixed and passed through the floor to the level below.

As well as the four storey mill there was the throwing room, glaze room and a very big kiln shed.

The kiln we built was large. To load it we would walk in carrying the saggars. These are fireclay containers which we stacked up in piles called ‘bungs’.

The glaze firing lasted 48 hours and contained some 3,000 pots.

A lot of the pots went out by post to retail customers, and for packing we used to collect hay from the churchyard. It was cut by hand with a scythe, or in difficult places a sickle, a laborious business, so the churchwarden was only too glad to have someone turn it and take it away.

As a packing material it was excellent and smelled lovely, so that our customers often thanked us not only for the pots but for the lovely country smell of hay.